News

MFA Professor Biswamit Dwibedy Releases a Genre-Bending Memoir and his Fourth Poetry Collection

October 22, 2025

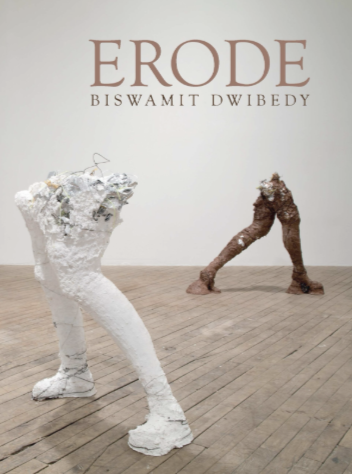

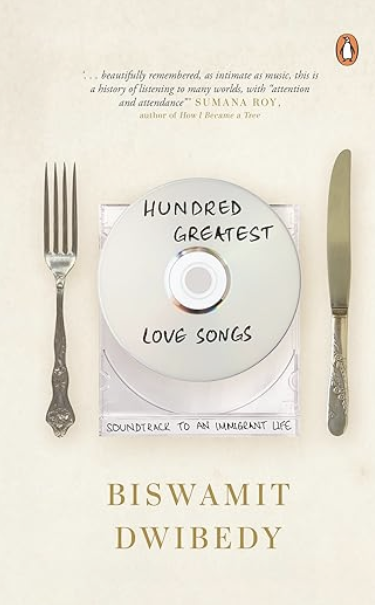

This fall, poet and AUP professor Biswamit Dwibedy is celebrating the publication of two ambitious new works: Erode, a poetry collection published by Litmus Press, and 100 Greatest Love Songs, a genre-bending memoir out with Penguin India. Both projects are deeply personal and testify to Dwibedy’s long-standing approach to writing as experimentation. Together, they form a dual portrait of a poet who teaches as he writes, and writes as he lives.

Erode, Dwibedy’s fourth collection of poems, is an expanded version of his debut collection Ozelid (2010), a work that has remained meaningful for him over the years. Erode includes a series of poems he had originally written when he returned to India from the United States in 2008. In the book, which is typographically daring and rich with accidental beauty, Dwibedy revisits some of his most formative experiences with language and literature, including the processes of erasure and collage, which are a crucial part of the curriculum in his poetry classes. “A poem is both a sonic experience and a visual one on the page,” Dwibedy says. He likens the act of writing poetry to sculpture, where editing erodes away all that is unnecessary.

100 Greatest Love Songs, published by Penguin in India and forthcoming in the US, is something altogether different—it’s an autobiography told in the second person, in which none of the characters have names. Based on his experiences working at a greasy diner in Iowa City and studying at Bard College, where Dwibedy earned his MFA, each of the book’s 100 short chapters revolves around a song that has been important for Dwibedy. “Think of it less as autobiography, and more as a playlist,” says Dwibedy. “Music was always playing in the background at the diner,” he recalls—“Whitney Houston, Madonna, and Mariah Carey, as well as artists like Cat Power, Animal Collective, and Björk.” The book is also an ode to the poets he loves and teaches regularly—Cole Swensen, Fanny Howe, Rosmarie Waldrop, and Leslie Scalapino—Dwibedy’s own teachers from years past. Ultimately, the collection discusses how Dwibedy was able to carve a different path for himself through poetry. “It was how I learned English,” he says, “watching Sex and the City, listening to pop songs, reading poetry.” The result is an experimental memoir that documents Dwibedy’s life during the years he was writing Ozalid, particularly his time in Iowa, where he worked as a waiter for a decade. It also reflects on how memory is organized, and how stories can be told through fragmented forms.

Dwibedy’s teaching has been a key influence on both books—and vice versa. At AUP, where he co-leads the new MFA program in Creative Writing, Dwibedy’s courses emphasize generative experimentation, something which has led students to write a series of 100 tankas, draft a sonnet every day of April, for example, or create chapbooks in advanced workshops that are both based in research and play with form; his students often include visual material in their books, or create poetry that is as visual as it is lyrical. “A lot of what I teach ends up in my books,” he says, “and what I write feeds back into how I teach.” The energy of the classroom is reciprocal. “Students always go way beyond what I expect—in form, layout, and genre,” Dwibedy explains, glowing. He encourages them to think across disciplines and formats when working on their projects.

He shares his creative process freely with his students, through conversations in class, particularly about the use of historical archives to tell forgotten or overlooked stories. One of his recent projects, The Hindoostani Coffee House, is based on immigrant life in early 19th century London. A part of the text was curated by the poet Claudia Rankine for her show “For Real For Real.” This is part of Dwibedy’s ongoing interest in how creative writing can honor the lives and voices that might otherwise be erased.

Given his own practice, it’s no surprise that Dwibedy encourages students to jump between genres. “Memoir, poetry, fiction—it’s all about discovering how new stories need to be told in ways that push the boundaries of a genre,” he explains. “I always ask students to find the connection between form and content, to juggle many voices and genres at once. It is more about being able to follow the form or voice in which a certain idea or story needs to be told, than finding ‘a voice of your own.’ As writers, we must be able to speak in many languages, many voices. We must be in conversation with voices from the past.”

As the co-director of AUP’s MFA in Creative Writing, he can’t help but see the publication of these books that reflect on his beginnings as a full-circle moment. “The MFA program wouldn’t have been possible without ideas I was exposed to during my time as an emerging poet, as I followed my favorite writers from Iowa to Bard,” says Dwibedy. “And now, many of those same writers come to AUP to speak with my students. That, I think, is very poetic.”